Advancing Global Health Equity

ENHANCING CLINICAL TRIALS ACCESS AND COOPERATION TO SAVE MILLIONS OF LIVES FROM CANCER

- Introduction

- Global Health Equity

- Clinical Trials and the Fight Against Cancer

- Benefits of China’s Participation

- Obstacles, Skepticism and Responses

- Authors

- Acknowledgements

- References

Introduction

Cancer accounts for approximately 10 million deaths globally each year. Too many of these 10 million lives lost to cancer could be saved through enhanced international cooperation.

According to a study by the Bloomberg New Economy International Cancer Coalition, global regulatory harmonization for clinical trials and cancer therapy approvals could reduce global cancer-related deaths by an estimated 10% to 20%, or 1 to 2 million lives per year.

However, studies have shown that the current patient participation in oncology clinical trials is fewer than 5% globally with significant disparities among communities, even though more than 70% of the same patients are either inclined or very willing to participate in such trials

This first Cure4Cancer report of a policy series underscores the potential impact of international regulatory harmonization, with a case study of China joining Project Orbis. Such cooperative initiatives could greatly streamline international regulatory processes and bolster global health equity by expanding access to clinical trials and precision oncology worldwide.

Download the report here

Global Health Equity

Health equity is defined as the absence of avoidable differences based on sex, gender identity, race, ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation, or other factors that affect access to care and health outcomes.

Achieving global health equity requires the identification and elimination of factors that create inequities in health outcomes in living conditions; education; socioeconomic status; geography; access to quality, culturally competent, and affordable health care; and so on.

The significance of equity in oncology R&D cannot be overstated. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, an estimated $50 billion was spent annually on oncology R&D by the biopharmaceutical industry; the cost of clinical trials, which often last many years, is exorbitant, amounting to tens or hundreds of millions of dollars for each trial. Today, oncology R&D is estimated to cost the industry $80 billion per year according to the recent analysis.

Advancing global health equity, therefore, is not only a prerequisite for the sustainable development of global public health but also a strategic business decision. Developing international clinical trials could prove essential for advancing global public health equity. International clinical trials stand to increase patient access in global communities, diversify participants, accelerate R&D timelines, reduce cost, and increase the worldwide impact of scientific results.

Increasing the percentage of patients from diverse backgrounds who have access to clinical trials (from the current fewer than 5% through international collaboration), could accelerate accrual and shorten the drug approval timeline from the traditional 10–15 years to a 2–3 year process. This would save millions of patients waiting for treatments, lower the costs associated with clinical trials, open new markets and revenue streams for pharmaceutical companies: these have the potential to contribute significantly to global health equity.

What are the barriers to global health equity?

China, a country with the world’s largest cancer burden, has not been sufficiently included or integrated into the international R&D and regulatory approval framework in terms of relevant data and cases over time.

This also epitomizes the situation of many low- and middle-income countries with large cancer patient populations lacking representation in the international regulatory landscape.

As the global cancer burden is expected to continue to rise, the importance of equity in oncology R&D is gaining increasing recognition in both industry and academia. To integrate equity more deeply into oncology R&D, therefore, is not only a moral imperative but also a sound policy and business strategy that can lead to significant advances in cancer care.

Clinical Trials and the Fight against Cancer

Clinical trials are research studies to test and evaluate how innovative cancer drugs, vaccines, and technologies perform for patients.

Continued human progress in cancer treatments and prevention is deeply reliant on access to clinical trials. By testing innovative therapies, these clinical trials have the potential to both save the lives of trial participants and expedite regulatory approvals of new cancer treatments that can help millions more patients battle the disease.

The clinical trial development process is constantly changing in a number of ways. For example:

- The technology for matching clinical trial patients to interventions based on AI algorithms is evolving.

- Regulatory agencies such as the U.S. FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have created novel and accelerated regulatory pathways to increase the flexibility of clinical trials design and execution.

- Remote monitoring and clinical trial participation technology have the potential to decentralize the distribution of clinical trial patients away from major academic centers.

In sharp contrast to the breakthroughs and innovations in clinical trial development, there is also growing attention to the barriers that impede the advancement of cancer treatments research and development. Among these barriers, first and foremost is the lack of patient access to clinical trials.

The main barrier to finding lifesaving new cancer treatments or preventions is the time it takes to conduct clinical trials.

Many factors contribute to this problem, but inadequate international regulatory coordination and cooperation is one of the more prominent ones: bureaucratic red tape, gaps in regulatory systems, less standardized institutional review boards with delays in clinical trial activation, and a lack of policy coordination between government regulatory agencies in different countries substantially limit clinical trial progress by resulting in delays in regulatory review and approvals, the cancellation of international cooperative regulatory projects, and grants and funding expirations while waiting for regulatory approvals.

Better international standardization of clinical trials and their approvals can shorten the time needed to roll out a new cancer treatment from the traditional 10–15 year process to a 2–3 year timeline, accelerating biological discovery and having a positive impact on future funding and investments in more clinical trials.

It can also lead to more affordable cancer treatments for more patients globally, more international academic collaboration and research output, and reduced R&D costs for all stakeholders. Conversely, if we continue with the current status quo of fewer than 5% clinical trial access with an expensive and lengthy R&D timeline, it is safe to say that the Cure4Cancer or the eradication of cancer as a major cause of death will not be achieved.

REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS SUPPORTING GLOBAL COOPERATION AGAINST CANCER: CANCER MOONSHOT WITH A CASE STUDY ON PROJECT ORBIS AND CHINA

Cancer Moonshot, launched in 2016 and reignited in 2022, is a signature project of U.S. President Joe Biden that is led by the White House, in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and other federal agencies. The White House Cancer Moonshot aims to “end cancer as we know it,” specifically reducing the cancer death rate in the United States by at least half by 2047. Cancer Moonshot currently supports more than 70 programs and more than 250 research projects housed at the NIH.

The FDA Oncology Center of Excellence (OCE) has already made progress toward this goal with the 2019 launch of Project Orbis, an initiative to set up an international regulatory infrastructure for simultaneous submission, review, regulatory action, and approvals of clinically significant new cancer treatments in multiple countries, instead of separate sequential applications in each country, thus avoiding duplicity and shortening the time needed for patients to access innovative cancer medicines. Current Project Orbis Partners (POPs) include the regulatory health authorities of Canada, Australia, Switzerland, Singapore, Brazil, the UK, and Israel.

Since its inception, Project Orbis has led to the multinational approval of 75 oncology drugs for patients across the world. Major oncology disease categories were represented in the Orbis submissions, including solid tumor and hematologic malignancy indications.

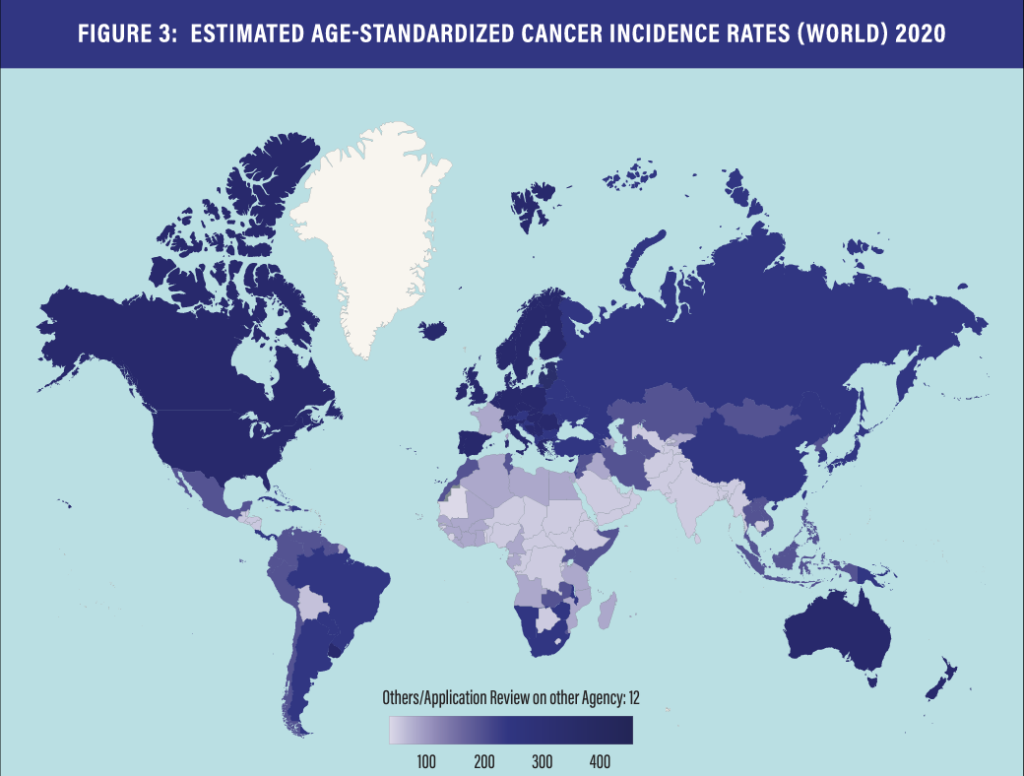

However, the effectiveness of the project needs to be further developed from several aspects, including the limitation of the number of member countries and the limitation of the amount of corresponding data. Its current member countries account for only 21.64% of new cancer cases worldwide in 2020 – hardly representative of the vast global cancer population, leaving shortcomings in the timeliness, diversity, and equity of the programs it supports for approval.

Cancer experts and regulatory agency leaders from the United States and China have been discussing a potential agreement to collaborate in the fight against cancer through regulatory harmonization in multiregional clinical trials and the possibility of China joining Project Orbis. So far, China, with the world’s highest cancer patient population and potentially the most impactful partner in this effort, remains absent from the initiative.

The United States and China share a common international regulatory background and have a history of cooperation: both are members of the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) and have adopted international standards per ICH guidance documents, and each country has issued several guidance documents to further clarify respective regulatory requirements; thus, the bilateral review process would build on existing regulatory requirements and drive greater harmonization in regulatory decision-making.

China’s participation in clinical trials would yield manifold benefits for promoting public health equity, but it also faces obstacles and challenges.

Benefits of China’s Participation

POPULATION AND DATA: If China were to join Project Orbis, the number of new cancer cases in 2020 represented by the POPs would rise from 21.64% to 46.88%. Accounting for nearly 40% of the global annual cancer deaths, the prospect of the United States and China working together with other countries to fight the common enemy of humanity offers significant opportunity for success.

STANDARD SETTING: With the patient population and size of the China market, the global community is better served by including China’s regulatory agencies, cancer researchers, doctors, and industry leaders in the international standard-setting regulatory process. Simultaneous regulatory reviews allow global cancer breakthroughs to enter the China market earlier and impact more lives. Likewise, Chinese cancer breakthroughs through multiregional clinical trials could also greatly benefit patients in all POP countries.

URGENCY: China is the world’s No. 1 cancer hotspot, with more than 4.8 million new cancer cases and 3.2 million deaths annually. The United States follows as No.2 in cancer burden, with about 1.9 million cases and more than 600,000 deaths annually. This makes the people of the two countries the largest number of cancer patients and natural collaborators as epicenters for cancer research and clinical trials, as well as humanitarian need, to fight against cancer, their common enemy.

REDUCING COSTS FOR ALL: The bilateral review process has the potential to eliminate or reduce delays in regulatory approval of innovative drugs in either market, thereby enabling patients in both countries to gain earlier access to therapies with reduced time costs and less costly expenses. One of the core measurable benefits of Project Orbis is a minimization in the lag times between FDA approval and approval in POPs.

More data and lower regulatory hurdles translate directly into faster clinical trials and could lower costs for R&D. This has the potential to significantly improve the affordability of approved treatments for U.S. and global cancer patients and insurers, hence saving more lives.

IMPACT ON THE INDUSTRY: The more diverse infrastructure of approval frameworks and the faster approval timelines among participating countries, if achieved by China’s involvement in Project Orbis, can significantly improve the “return on” and the impact of clinical trials, which indicates substantial investment opportunities across the industry.

RECIPROCITY: The FDA has specific requirements for data quality and applicability through multiregional clinical trials, and these standards will be upheld and strengthened through Project Orbis, applying to all its members. Shorter approval timelines will benefit patients in both China and the United States, not to mention the rest of the world. And since the majority of the U.S. and international biopharmaceutical companies operate in both the United States and China, reducing the lag time for drug approvals in China and facilitating faster entry into the China market would benefit all such companies.

GLOBAL MULTILATERAL LEADERSHIP AND INNOVATION: China’s participation would provide a very strong incentive for other countries to join Project Orbis, further advancing the harmonization of international regulations, speeding up clinical trials, and saving more lives. This has the potential to firmly demonstrate U.S. global leadership and the ability to serve concrete global public goods. China has the same incentive.

STABILIZE U.S.-CHINA RELATIONSHIP AND PROMOTE WORLD PEACE: Genuine cooperation could help stabilize the U.S-China bilateral relationship, but unfortunately such opportunities are rare. But both countries have a strong national interest in reducing cancer’s death toll, and so Project Orbis could present one such chance for cooperation.

Obstacles, Skepticism and Responses

BIOSECURITY AND HUMAN GENETICS: Biosecurity around international clinical trials are of particular concern to U.S. citizens. However, the nature of Project Orbis is inherently secure, with only trial data (and no biological material) passing across international borders. Data sharing is key to the success of international clinical trials, and the sharing of cancer genetics has been routinely done in a secure, anonymous fashion for over two decades (see the publicly available Cancer Genome Atlas as a result of this). Continual compliance with existing regulations on human genetics will ensure no unnecessary delays to international clinical trials and breakthroughs.

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY PROTECTIONS: There are no concerns about Intellectual property (IP) protections within Project Orbis. International clinical trials are highly regulated and transparent. Secondly, clinical trials are intended to transfer scientific breakthroughs for which IP has already been patented and published, and to turn the IP into medical treatments that can then be made commercially available.

Authors

Bob T. Li,MD, PhD, MPH, Physician Ambassador to China and Asia-Pacific, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; Associate Professor of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine, Cornell University; Senior Fellow on Global Public Health, Center for China Analysis, Asia Society Policy Institute

Jing Qian, Co-Founder and Managing Director, Center for China Analysis, Asia Society Policy Institute; Advisory Board Member, Bloomberg New Economy

Greg Simon, Distinguished Fellow, Global Public Health, Center for China Analysis, Asia Society Policy Institute; Former President, Biden Cancer Initiative

Justin Finnegan, Founding Managing Director, Bloomberg New Economy, Senior Fellow on Global Public Health, Center for China Analysis, Asia Society Policy Institute

John Oyler, Co-Founder and CEO, BeiGene

David Fredrickson, Executive Vice President, Oncology Business, AstraZeneca

Chitkala Kalidas, PhD, Vice President, Global Head of Oncology Regulatory Affairs, Bayer AG

Shaalan Beg, MD, Vice President, Oncology, Science 37; Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Si-Yang Liu, MD, Visiting Investigator, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; Attending Thoracic Surgeon, Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute and Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital, Chinese Thoracic Oncology Group

Dorrance Smith, Media Advisor on Global Public Health, Center for China Analysis, Asia Society Policy Institute

Morgan Speece, Director of Operations, Asia Society Policy Institute; Project Manager, Center for China Analysis

Yi Qin, Junior Fellow on Chinese Society and Public Health, Center for China Analysis, Asia Society Policy Institute

Sepideh Shokrpour, Coalitions Manager, Bloomberg New Economy

Mary Gospodarowicz, MD, FRCPC, FRCR(Hon), Princess Margaret Cancer Center, University of Toronto

Olufunmilayo I. Olopade, MBBS, FACP, OON, Walter L. Palmer Distinguished Service Professor of Medicine and Human Genetics, Center for Global Health, University of Chicago

Otis W. Brawley, MD, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Oncology and Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins University

Bobby Daly, MD, MBA, Assistant Attending in Thoracic Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

Acknowledgements

- Asia Society Policy Institute

- Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK)

- Chinese Thoracic Oncology Group (CTONG)

- Bloomberg New Economy International Cancer Coalition

- Forbes China

- Thoracic Oncology Group of Australasia (TOGA)

- AstraZeneca

- Bloomberg New Economy International Cancer Coalition

His Excellency the Honorable Dr. Kevin Rudd, former Asia Society Global President and CEO, Stefan Oelrich, president of Bayer Pharmaceuticals.

We also acknowledge the work of countless others who helped in the creation of this report, including Gary Rieschel, Lulu Wang, Orville Schell, Shane Williams-Ness, Duncan Clark, Peter Jakes, as well as Susan Galbraith, Shira Gerver, and Megan Yuan from AstraZeneca and Shreya Jani and Mark Lanasa from BeiGene. Colleagues at Asia Society include Debra Eisenman, Kevin Hogan, Danny Russel, Rorry Daniels, Susie Jakes, Alexandra Zenoff, Linda Benson, Anisa Chugthai, as well as Bates Gill, Nathan Levine, Wendy Ma, Inger Marie Rossing, Johanna Costigan, and Patrick Beyrer at the Center for China Analysis, Asia Society Policy Institute.

References

1 “What Are Clinical Trials?” National Cancer Institute. Accessed May 1, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/ treatment/clinical-trials/what-are-trials#:~:text=Through%20clinical%20trials%2C%20doctors%20determine,people%20 during%20and%20after%20treatment.

2 Daly, B., Finnegan, J., Li, B. T., and Qian, J. “We Need a Global System for Testing and Approving Cancer Treatments.” Harvard Business Review, October 18, 2022. https://hbr.org/2022/10/weneed-a-global-system-for-testing-and-approving- cancer-treatments.

3 Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R.L., et al. “Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries.” CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 71, 209-249 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3322/ caac.21660.

4 Li, B. T., Daly, B., Gospodarowicz, M. et al. “Reimagining Patient-Centric Cancer Clinical Trials: A Multi-Stakeholder International Coalition.” Nat Med 28, 620–626 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01775-6.

5 “Health Equity.” World Health Organization. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.who.int/health-topics/health- equity#tab=tab_1.

6 “Increasing Access for Clinical Trials.” Data from Bloomberg New Economy International Cancer Coalition. Est. publication in 2023.

7 “Clinical Trials.” World Health Organization. Accessed April 15, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and- answers/item/clinical-trials#:~:text=What%20is%20a%20clinical%20trial,referred%20to%20as%20interventional%20trials.

8 “Diversity and Inclusion in Clinical Trials.” National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Accessed June 28, 2023.

9 Flannery, R. “U.S.-China Collaboration Could Cut Development Time, Cost for New Cancer Treatments.” Forbes, March 27, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbeschina/2023/03/22/us-china-collaboration-could-cut-development-time-cost-for- new-cancer-treatments/.

10 “Global Cancer Data by Country: World Cancer Research Fund International.” WCRF International, April 21, 2022. https:// www.wcrf.org/cancer-trends/global-cancer-data-by-country/#:~:text=Globally%2C%2018%2C094%2C716%20million%20 cases%20of,women%20(178.1%20per%20100%2C000).

11 “Definition of a Clinical Trial.” University of California–San Francisco Clinical Research Resource HUB. Accessed August 18, 2023. https://hub.ucsf.edu/clinicaltrialsgov-definition-clinical-trial.

12 “Notice of Revised NIH Definition of ‘Clinical Trial.’” Notice Number: NOT-OD-15-015. Release Date: October 23, 2014. NOT- MH-20-105. Issued by National Institutes of Health (NIH). https://hub.ucsf.edu/clinicaltrialsgov-definition-clinical-trial.

13 “Project Orbis: A Framework for Concurrent Submission and Review of Oncology Products.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed March 3, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/oncology-center-excellence/project-orbis.

14 “Project Orbis Approvals.” Oncology Center of Excellence, U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Accessed July 7, 2023. https:// www.fda.gov/media/169691/download?attachment.

15 R. Angelo de Claro, Dianne Spillman, Lauren Tesh Hotaki, et al., “Project Orbis: Global Collaborative Review Program,” Clinical Cancer Research 26, 6412–6416 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-20-3292.

16 Masson, G. “FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence Slowed Launch of New Projects in 2022 to Focus on Trial Modernization.” Fierce Biotech, February 7, 2023. https://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/fdas-oncology-center-excellence-slowed-launch- new-projects-2022-focus-4-specific-programs.

17 Ferlay, J., Ervik, M., Lam, F. et al. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Indonesia Fact Sheet. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. Accessed July 10, 2021. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/360- indonesia-fact-sheets.pdf

18 Puspitaningtyas H, Espressivo A, Hutajulu SH, et al. “Mapping and Visualization of Cancer Research in Indonesia: A Scientometric Analysis.” Cancer control : journal of the Moffitt Cancer Centervol 28, 10732748211053464 (2021). https://doi. org/10.117710732748211053464.

19 Howlett, J. IAEA Department of Technical Cooperation and Gil, L. IAEA Office of Public Information and Communication. “Indonesia Plans to Increase Access to Cancer Control.” International Atomic Energy Agency. February 6, 2018. https://www. iaea.org/newscenter/news/indonesia-plans-to-increase-access-to-cancer-control.